Family History

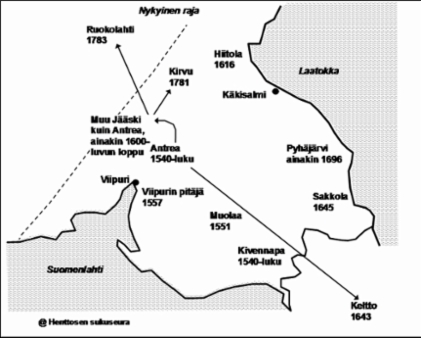

The different branches of the Henttonen family come from the Karelian Isthmus, where they existed at least in the 1540s. The oldest urbariums (registers) in the area include two Henttonens as farmers in the village of Venepohja in Jääski, which later became known as Henttola.

16th and early 17th century documents contain quite a few Henttonens, but it is unclear how they are related to later Henttonens. This requires further investigation.

Most of the present Henttonens are descended from Pietari Ollinpoika (Per Olofsson = Olli's son Peter), and his son Olli Pietarinpoika (Olof Persson = Peter's son Olli) who were farmers in Henttola in Jääski (Antrea). Olli was a dragoon (Hakkapeliitta) of the heavy cavalry of Gustav II Adolf in the Thirty Years War. He fell in Poland in 1649. Another Olli Pietarinpoika can be found in the documents of the same period. By the end of the 1630s dragoon Olli was already elderly, joining the Vyborg Regiment in 1645, and at the time of the supposed fall in 1649, at least 70 years old, which raises the question of whether two persons with the same names are mixed.

This ambiguity requires further investigation.

Corporal Tuomas Ollinpoika Henttonen was a dragoon and fell in Poland in 1656. He was the son of the above-mentioned Olli Pietarinpoika. Their relationship is found in district court documents. According to them Olli's son Antti (genealogy chart 8 in the family book) and Antti's brother's son Matti Tuomaanpoika (genealogy chart 706) litigated against against each other. The dispute on the right to be the master of the farm was split, that is, each received half.

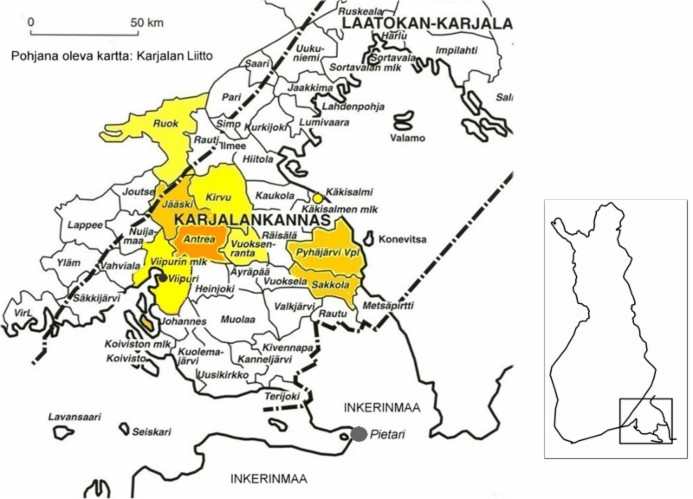

The family branches of Pyhäjärvi and Sakkola are also most likely descendants of Henttonens of Henttola in Jääski. At least one Henttonen who moved to Pyhäjärvi in the 17th century, came from the Province of Vyborg, according to district court documents in the Kexholm County. This must mean Henttola in Jääski. Unfortunately, there is a gap in the documents of the Kexholm County for several decades in the early 18th century, and so far no exact lineage has been found between the Henttonens of Pyhäjärvi and Sakkola and the later 18th century Henttonens.

Some Henttonens moved to Ingria in the 1640s, where they still lived at least in the early 20th century.

Henttola, which belonged to Antrea since 1721, is thus surely the birthplace of most of the Henttonen branches.

Wars in the regions where Henttonens lived

There have been numerous wars in the regions where Henttonens lived. As a result, the border between Sweden and Russia split the region in different places at different times. The eastern parts of the Isthmus, including Pyhäjärvi, alternatively belonged to Sweden and Russia.

In the aftermath of the Great Northern War in 1721, the southern and eastern parts of the Isthmus ended up in Russia. The border crossed Jääski and Kirvu, and Henttola stayed in Russia. The villages of Jääski and Kirvu on the Russian side became the civil parish of Antrea. The whole southeastern Finland up to the Kymijoki River was forced from Sweden to Russia after the Russo-Swedish War, in 1743.

As a result of the Finnish War (1808-1809), more areas of Sweden came under Russian rule. As to the Finnish-speaking regions, only part of the province of Länsipohja (Västerbotten) remained in Sweden. The Tsar promised Finland autonomy. In 1812 the new territories occupied by Russia were annexed to the Finnish-speaking territories which Russia had occupied during the time of the Great Northern War and the Russo-Swedish War. These old occupations began to be called Old Finland. The inhabitants of Eastern Isthmus, including those living in Pyhäjärvi, had almost become serfs, being subservient to Russia, and during the autonomy they had to buy back their own lands. The other Henttonens did not have this great expense, since elsewhere most Old Finland farmers had remained independent and owned their own farms.

From time to time, Henttonens were able to live in peace and cultivate their fields. Savilahti, the shallow bay of Vuoksi, used to extend to Henttola in Antrea, which explains the old name of the Henttola village, Venepohja. The flat shores were plagued by floods in the Vuoksi River, and agriculture was adversely affected. For this reason, the inhabitants in Antrea were given permission by the authorities to clean the Kiviniemi rapids. Thus the Suvanto-Taipale route became the main route of Vuoksi, instead of the Kexholm route. The surface of Savilahti(bay) decreased by more than three metres. Most of the alluvial soil was dried into fields. Several villages in the area are collectively known as Savilahti.

Henttonens in their home regions were Finns until the end of the Winter War of 1939-1940, regardless of which country they belonged to. Finns were not the only ones living in Vyborg, there were also non-Finns, notably Swedes, Germans and since the 18th century, Russians.

The Soviet Union started the Winter War on November 30, 1939. After the end of the Winter War, the population of the Isthmus, Ladoga Karelia and Border Karelia had to leave their home regions. The peace after the Winter War lasted for over a year, until the Continuation War broke out in June 1941. Finland occupied the lost territories plus some extra areas, and people were able to move back to their homes - though not everyone did. Many of those who moved back home had to repair their homes and cowsheds etc. that had been damaged during the war or occupation. Many homes and buildings were completely destroyed.

After the Continuation War in 1944 the Russians demanded that the Karelian Isthmus belong to Russia. The Soviet Union again ordered the inhabitants to leave the area. The Soviet Union shut down practically all of Karelia for many decades. Henttonens and other former inhabitants of the Isthmus did not get to see their centuries-old home regions until the collapse of the Soviet Union. There were harsh surprises. The inconceivable devastation had extended - and still extends - to graveyards, gravestones and grave monuments of the submitted area. Next to the church of Kirvu, the Russians had set up a garrison and built an artillery depot just on the graveyard, which was only moved away from there in the late 1990s. Countless houses and villages had been destroyed after the war, not during the war. Strangers had moved to houses that had not been destroyed. However, sociable Karelians have made acquaintances, even friendships, with some of the occupiers of their home villages and homes.

Origin of the Henttonen name

Pirjo Mikkonen & Sirkka Paikkala: Sukunimikirja (Surname book) (revised edition, Otava 2000):

"The ancient German personal name Heimrich has apparently spread in many popular variants in Finland long before the commemoration of National Saint Henry's Day in our country. Numerous variants include Henti, Hentti, Hentto, Hentu, Henttu, all of which have become surnames in South Karelia, especially in North Ostrobothnia." --- "Various variants have not been very carefully separated in Karelian sources from the 16th and 17th centuries: at that time, the surnames Henttinen, Hentilä, Henttonen, Henttu, Henttunen, Hentula and Hentunen do not appear to have been differentiated; more uncertainty has arisen because of spelling."

The earliest Henttonens, Henttinens, Hentunens et al

As far back as the 16th century, first names were often written in Finnish, for example, Antti or, according to Swedish spelling, Anti, but after that completely in Swedish, for example, Anders and not Antti. Church books used - besides Swedish - Latin, for example the name Andreas in the late 18th century. In Old Finland, that is, in the area that Russia received from Sweden in the peacemaking processes of 1721 and 1743, the language of the documents was German, before autonomy.

Church books had to be written in Finnish in Finnish-speaking parishes as late as 1880, and they also started to write the first names in Finnish. Until then, Finnish surnames and place names were often spelled according to Swedish spelling. Spelling varied because the scribes did not always know how to spell the name. In old documents, first and last names were sometimes written in lower case. In the 18th century and in the early 19th century, the Eastern Finnish suffix "-nen" actually had "-in" or "-inen" suffixes, such as Henttoin and Henttoinen.

The later western influence changed them to their present form. The spelling of the name Henttonen became established only after the mid-19th century.

The aforementioned surname book by Mikkonen and Paikkala lists among others the following Henttoset, Henttuset, Henttiset found in old documents:

- in Jääski 1549 per henton, 1558 p henttoine(n), 1554 peer hentulan, 1558 Tomas henti and Tomas petarin poi(ca) hentu, 1564 Tomas henttuin(en)

- in Muolaa 1551 Bertill Hendoijnn,1565 henduine(n), 1563 Per Henttine(n)

- in Vyborg civil parish 1557 h Hendoine, 1559 Hen(rik) hentti(nen)

- in Kivennapa 1566 Matti Henduine, 1558 M Henttonn

- in Hiitola 1616 Huodar Hentoinenn

- in Rautu 1617 Jörenn Henduin

- in Suistamo 1618 Rigo hendunen

- in Sakkola 1645 Hanss hentoinen, 1647 Henttoinen.

Professor Veijo Saloheimo, in his book "Viipurinkarjalaiset kotona ja maailmalla" (Publication of the Finnish Genealogical Society 57, Helsinki 2006), modernized the old unsteady writing patterns and lists the following Henttonens:

- in Antrea in the 1540s: two

- in Kivennapa Heino and Olli Henttonen in the 1540s

- in Suistamo Paavila Henttonen in 1618

and the following Hentunens:

- in Muolaa Paavo Hentu in the1540s

- in Jääski Lasse 1544

- in Ahjärvi of Kivennapa Ihannus 1560, in Pihlainen Matti

- in Vammelsuo of Uusikirkko Pekko 1560 and in Ino Vesteri Hentunen

- in Ruokojärvi of Impilahti Riiko Hentunen 1618

- in Suistamo Paavila Hentunen in 1618

- in the village of Wenehpohja in Jääski in 1544.

Henttola (which later belonged to Antrea) was then called Venepohja because the shallow Vuoksi bay, Savilahti, extended to Henttola.

Henttonens can be found in the Kexholm County Court records as follows:

- Anders (Antti) Hentzinen (later Hentoinen) in 1657 - at least 1671, lived in Miissua of Pyhäjärvi, near the border of Sakkola.

- Peter, Lars, Anders and Clemet Hentoinen, all sons of Anders mentioned above, in the late 17th century. At least three of them had sons. Peter had a son, Mats (Matti),

possibly the father of Adam (Aatu) Henttonen. One of Henttonen's lineages

begins from Adam, cf. genealogy family chart 2606. - Sigfred (Sihvo) Hentoinen lived in the Haitermaa of Sakkola (Lobrola) at least 1668-1695. His lineage begins from the page 471 in the family book.

All Henttonens, Henttinens, Henttunens, etc.found in the earliest documents are not listed above.

Extension of Henttonens before the 20th century

Parish registers begin in various parishes of the area in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. There are long gaps in the documents during the Great Northern

War and the Russo-Swedish War. Migrants are not always easy to find, not even

by help of parish registers, but of course it was more difficult without them.

Professor Veijo Saloheimo has studied those who had moved to Ingria and in the population register of that period he found Heikki Henttonen, whose family of three had moved from Savilahti to Keltto in Oserka (register KA 9656: 779v, see Veijo Saloheimo: Inkerikkoja, savakkoja ja äyrämöisä. Inkerinmaan tulomuuttajat ja sisäiset liikkujat vuoden 1643 henkikirjan mukaan. Joensuun yliopisto, Karjalan Tutkimuslaitoksen moniste No 10/1991).

The Thirty Years War swallowed more and more Finnish men. Taxation was also extremely harsh. For the Finnish farmer, the 17th century was a more difficult time than almost any other century. Not surprisingly, many tried to avoid taxes or

recruitment, including Hannes Henttonen from Henttola in Jääski by escaping to Käkisalmi Province in 1640.

The western part of the Karelian Isthmus used the Western Finland method, where the inhabitant was given the surname according to the house and not by inheritance from his father. This was quite common in the Vyborg province, and also in Jääski and St. Andrea there are cases where the surname is not inherited. At least in 1723 there was a village called Henttola in Revonsaari which was in the parish of Johannes (see Population Register of the Vyborg Province 1723, mf ES2693). Some of its inhabitants were documented with the surname Hentula, Hentola or Henttola since the late 18th century, and others, especially in the 19th century, under the name Henttonen.

Quite a few people moved internally in St. Andrea and Jääski since the 18th century. Several families moved from the village of Henttola in Antrea to Hyppälä and Rossila in Jääski at the late stages of the Russo-Swedish War or after the end of 1742-43.

It was difficult for the Henttonens in Pyhäjärvi to move away in the 18th century and even in the early 19th century, because the Russians had plunged them almost into serf status.

In the 18th century, the new settlements were as follows:

- Käkisalmi (from Pyhäjärvi?) at the latest in the 1760s

- The first Henttonens of Kirvu from Hyppälä in Jääski to Lietlahti (several families) in 1781

- The first Henttonens of Ruokolahti from Hyppälä in Jääski to Suikkala (several families) in 1783.

A few Henttonen families lived in the Vyborg province at the latest in the 1790s, and in 1794 at least one man moved from Savilahti in Antrea to Kavantjärvi in the Vyborg Province, to live in his wife's house as a son-in-law.

Unfortunately, there is a gap in the confirmation and church documents of the Vyborg Province in the late 18th century, so it is difficult to determine since when the first Henttonens lived there. In the 19th century, some Henttonens moved to work in St. Petersburg. Apparently Henttonens did not move outside South Karelia and Ingria until the late 19th century or the early 20th century.

DNA research supporting genealogy

Currently, genealogy can go back to prehistory, without names, dates, and exact locations, though.

People have hereditary characteristics in their chromosomes, or more precisely, in the DNA molecules contained in the chromosomes. A man inherits the Y chromosome from his father, who inherited it from his father, who in turn inherited it from his father, etc. On the basis of certain markers of the Y chromosome, men are grouped into haplo groups, or genetic "clans". With enough knowledge of the genes of different nations, comparisons can be used, over tens of thousands of years, to determine where in the world the genes of the male-father-father-etc chain come from.

Likewise, mitochondrial DNA analysis can be used to determine the ancestral movements of both male and female maternal relatives, i.e., the origin of the genes of the maternal-maternal etc. chain. Women are also grouped in haplo groups.

Several laboratories conduct DNA tests to determine the relationship between different families when it cannot be determined by genealogy in the absence of archival sources. Although the method has its limitations, it can still find genetic relatives in surprising countries and places. A common ancestor may have lived hundreds of years, even thousands of years ago.

Own sample?

More than 10,000 Finns have ordered a sampling kit from the website of the Finland DNA project http://www.familytreedna.com/public/Finland

Packaging and corresponding research cost start from less than hundred euros, depending on how extensive study you want to commission. The DNA sample is carefully taken from the inside of the cheeks and shipped to the USA where it is analyzed anonymously. The results are not sent to anyone; they are only on the Internet and can be seen by entering the ID code of the package. The result is the code for their genetic haplogroup, or "clan", and the approximate geographical route through which their own genes have probably come from East Africa during tens of thousands of years. That's where we all come from, descendants of "Adam and Eve" or really descendants of "Adams and Eves". They had a small tribe, and all men had the same, and all women the same haplotype - or at least those whose offspring live today. If you wish, you can enter your name and email address in the American database, in exchange for the email addresses of your closest genetic relatives in the database.

If you wish, you may authorize the publication of the name, place and date of birth, and date and place of death of the oldest known father-father-father, etc. (or mother-mother-mother, etc.) on the above American site . There are clear maps of places of birth, both in Finland and around the globe. You can also easily find the closest paternal and maternal genetic relatives in Finland. Your name will not appear on the Internet, and your ancestors' information can be deleted there.

DNA Testing and Origin of Henttonens?

The Finno-Ugric peoples' kinship is not based on race or culture, but linguistic kinship. Although the common language of origin is from the East, the Urals or the Volga bend, according to DNA studies, about one-third of modern-day Finns' male ancestors and about half of the female ancestors have come from the West during several thousands of years. Old-school textbooks told how Finns came here as one group about 2000 years ago, but this has been found to be a false statement several decades ago. People have lived here continuously since the end of the Ice Age, and we have genetic heritage from the people who lived here several thousands of years ago.

Genealogy has not been able find out whether all of the Henttonens' family branches are of the same origin. An interesting question is also whether the Henttonens, the Henttinens, the Henttunens, the Hentus, etc. are of the same origin. These things could be solved with DNA tests.

If you are testing your DNA, it would be a good idea to mention it to the chairperson of the family association. Also tell the origin and village of your family branch and your haplogroup.